Federal Government Moves to Shore Up Critical National Security

The Colonial Pipeline attack in 2021 was a turning point for critical infrastructure in the U.S. When a ransomware attack on a pipeline operator’s administrative network metastasized into soaring gasoline prices across the eastern seaboard; you’d better believe that policymakers were watching. The race was on to protect critical national infrastructure (CNI)—the backbone of private and public sector services that keep the country running.

The government moved to bolster protection at the federal level, leading to a strategy that included regulatory updates, full activation of unused authorities, and voluntary mechanisms to help harden CNI against attack. For example, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) published directives to bolster pipeline security. November 2021’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act carved out substantial funding for CNI projects at the local level. The Cyber Incident Reporting for Critical Infrastructure Act of 2022 (CIRCIA)mandated CNI incident reporting.

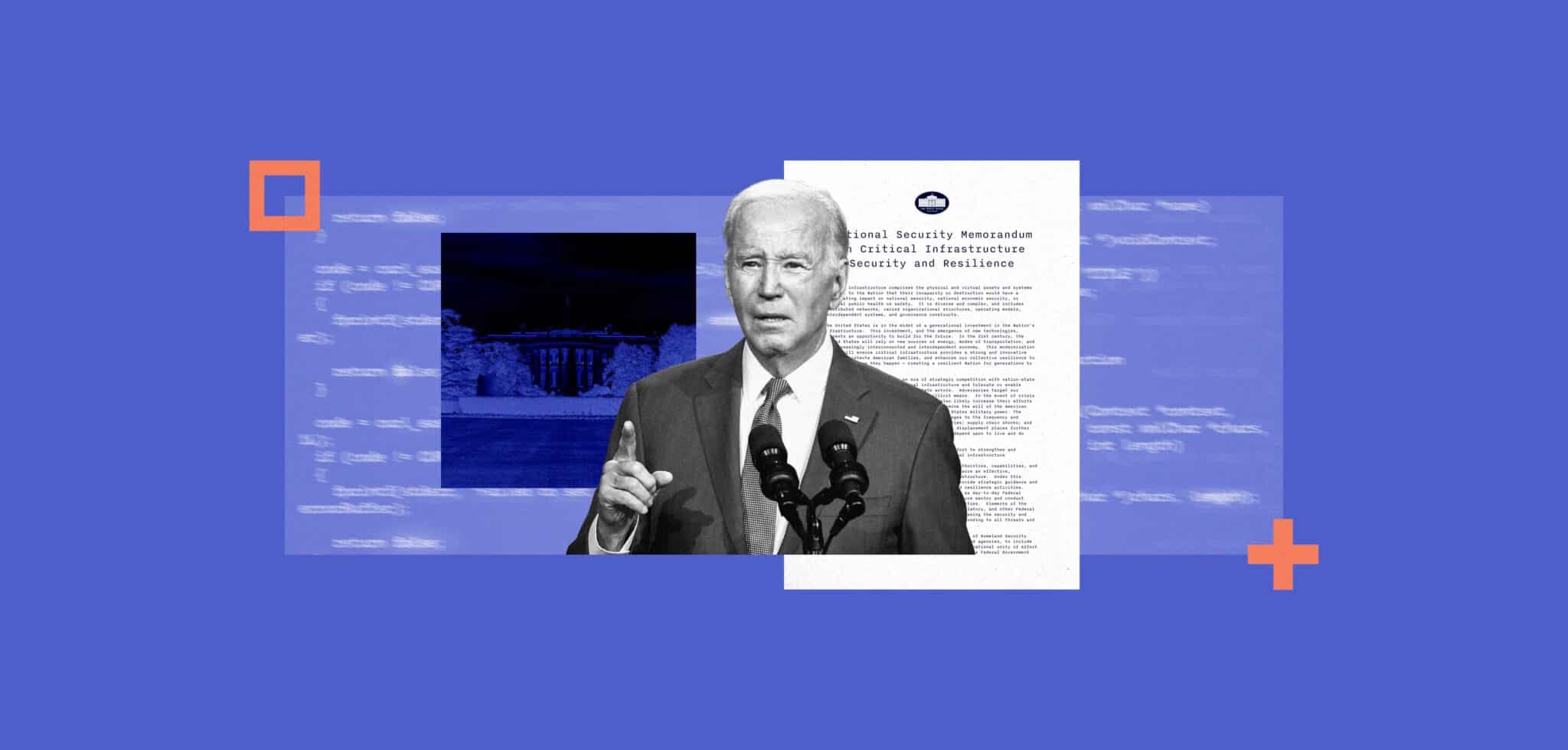

In April 2024, nearly three years after the Colonial attack, President Biden followed up efforts such as these with the National Security Memorandum (NSM-22) on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience, which set out the administration’s plans to protect CNI in more detail. This document replaces its predecessor, the Obama-era Presidential Policy Directive on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience (PD-21). However, it still retains many of PPD-21’s concepts, including the designation of 16 critical national infrastructure sectors ranging from chemicals to dams and financial services.

NSM-22 mandates minimum security and resilience requirements across critical infrastructure sectors. It puts the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) squarely in the driving seat to lead the government effort to protect the CNI, naming its Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) the National Coordinator for Security and Resilience. As part of this strategy, the Secretary of Homeland Security must submit a biennial National Risk Management Plan to the President.

The June guidance represents the DHS’s plan for this first biennial cycle. Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro N. Mayorkas outlined strategic guidance and national priorities for the next two years for critical infrastructure security and resilience efforts.

The new guidance focuses on five key areas, only some of which were tangentially mentioned in NSM-22:

- Addressing cyber and other threats posed by the People’s Republic of China

- Managing risks and opportunities presented by artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies

- Identifying and mitigating supply chain vulnerabilities

- Incorporating climate risks into sector resilience efforts

- Addressing the growing dependency of critical infrastructure on space systems and assets

These areas align with growing concerns about threats to CNI in the federal government. For example, in January, FBI director Christopher Wray testified to the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party that China was positioning itself to ‘wreak havoc’ on U.S. CNI.

The DHS guidance takes a collaborative approach. The DHS is enlisting the agencies responsible for these sectors to help take protective measures in these areas. It will also involve federal agencies, critical infrastructure owners and operators, and other government and private sector stakeholders.

Those protective measures don’t delve down into specific threats from tech like AI. Rather, they reflect those outlined in NSM-22 with a view to activating stakeholders. The first is to build resilience by creating an infrastructure that can recover quickly from attacks. This acknowledges that simply hardening infrastructure to stop attacks isn’t enough; operators must assume that some attacks will succeed.

Resilience measures include understanding system dependencies and anticipating potential cascade effects from attacks. The guidance also calls for cross-sector analysis of systemic weaknesses, pointing out that there are key resources on which many sectors depend. Energy is a prime example, as it serves the needs of all the other sectors. NSM-22 had already directed CISA to create a list of systemically important entities – dominoes that, if toppled, could also bring others crashing down.

Each sector’s agency must establish mandatory baseline resilience requirements, ideally using existing government guidelines and standards. This is something that the Center for Cybersecurity Policy and Law has highlighted: “it does acknowledge that voluntary approaches to security and resiliency have not been successful enough, and that mandatory minimum requirements are necessary,” says Ari Schwartz, coordinator at the CCPL.

A key challenge here will be enforcing these requirements across the public sector. The guidance suggests that agencies use a mixture of grant-making and procurement powers to make these baseline measures stick. This will also mean working with service providers (the guidance specifically calls out cloud providers) to ensure that their services are secure by design.

Responses from at least some sectors to recent CNI protection measures have been cautiously optimistic. For example, when the White House released NSM-22, the Association of State Drinking Water Administrators (ASDWA)responded: “While it’s unclear how the new NSM will directly impact the ongoing efforts to increase resiliency across the water and wastewater sector, ASDWA continues to engage with EPA and sector partners to support state and Federal activities to address all hazards, including the most recent efforts to standup a Cybersecurity Task Force for Water to address the growing cyber threats challenging the sector.”

The DHS guidance didn’t add a huge deal to the existing memorandum other than to clarify specific focal areas that have been much-discussed in various executive orders and cybersecurity strategies. However, it isn’t the only document that CISA has published on infrastructure resilience. In March 2024, it published an Infrastructure Resilience Planning Framework (IRPF) to help stakeholders plan for more robust infrastructure that is more resilient to attack. It recently released a playbook to accompany this framework. Work like this to sharpen operational resilience is ongoing and will culminate in a 2025 National Plan for Infrastructure Protection. This will replace a 2013 plan to reflect the government’s updated CNI resilience goals. It’s good to know that CISA has its eye on the prize.